Affirming citizens’ rights, the Supreme Court has sternly ordered the Maharashtra government to vacate two residential flats in South Mumbai that have been under police occupation since 1940 in the absence of a formal agreement or legal sanction. The decision pertains to a case titled ‘Neha Chandrakant Shroff & Another vs. State of Maharashtra & Others’, where the apex court overturned a 2024 Bombay High Court ruling that dismissed the appellants’ plea and advised them to seek civil remedies.

According to the petitioners, the flats were requisitioned by the police more than 80 years ago in order to maintain law and order during the turbulent period of the Independence movement, particularly due to frequent protests near August Kranti Maidan.

The Amar Bhavan building on AR Rangnekar Marg near the Royal Opera House. PIC/BY ARRANGEMENT

The petitioner approached the authorities concerned multiple times seeking the release of the flats from requisition after the crisis had subsided. However, possession of the flats was never returned. There were instances when even the monthly payments were irregular, necessitating ongoing correspondence regarding both the restoration of possession and payment of arrears. “The flats were not only kept vacant but also left in a state of disrepair, without proper maintenance or upkeep,” the petition reads.

A legacy of injustice

The dispute centres on flat nos. 11 and 12 on the third floor of the Amar Bhavan building at AR Rangnekar Marg in the prime location near the Royal Opera House. The then-owner of the flats, the father of the petitioners, had voluntarily permitted the police department to temporarily occupy the premises. Crucially, no written lease, licence or requisition order was ever executed. The only payments made were R611 per flat every month, which ceased altogether in 2008. The family repeatedly requested the return of the premises for their personal use and sent multiple legal notices, beginning in 1997. However, the state neither vacated the flats nor entered into any legal arrangement.

In 2009, the family finally moved the Bombay High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution seeking repossession of their property. Represented by Dr Sujay Kantawala, the petitioners cited multiple Supreme Court judgments to support their contention that continued occupation of the flats was unlawful and violative of their fundamental rights under Articles 14 and 300A.

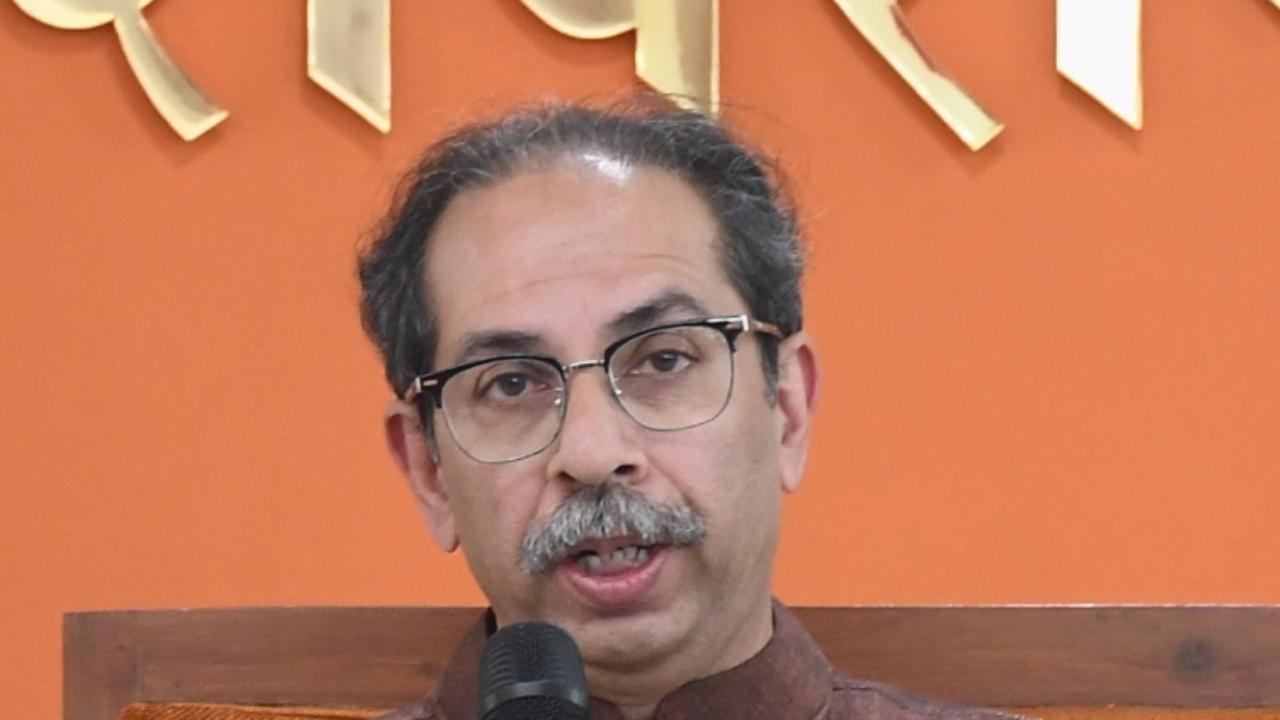

Advocate Dr Sujay Kantawala, who represented the petitioners in the Bombay High Court. File Pic/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

However, the Bombay High Court dismissed the writ petition on April 30, 2024, stating that the matter required a determination of facts unsuitable for writ jurisdiction and advised the petitioners to file a civil suit—a process that could have taken even more decades.

‘Insult to injury`

Delivering its judgment on April 8, 2025, a Supreme Court bench comprising Justices J B Pardiwala and R Mahadevan set aside the high court ruling, holding that the high court had erred in refusing to exercise writ jurisdiction in this exceptional case. “To ask the appellants to file a suit and recover the possession would be like adding insult to injury. How many years would it take for the litigation to come to an end? These are the hard facts high courts are expected to keep in mind in today’s times.”

The court criticised the high court’s narrow interpretation of “permissive possession,” noting that it failed to account for the extraordinary circumstances and passage of time since 1940. It emphasised that judicial discretion must be exercised contextually, especially where the state is seen squatting on private property without any legal authority for over 84 years.

Scathing indictment

During the hearing, the Supreme Court discovered that the flats were not even being used for official purposes. Instead, two families of police officers had been residing there for years, effectively enjoying prime real estate in South Mumbai. “Look at the conduct of the department. For the past eighteen years, even rent has not been paid,” the court noted sharply. “The department can very easily shift to any other place and allow the petitioners to use their own property.”

The court also pointed out that no lease deed existed, and information procured under the Right to Information Act confirmed the absence of any written requisition order or contractual agreement. The state, despite being offered multiple opportunities to settle the matter amicably, refused to act.

Earlier this year, the court had passed two interim orders, dated January 28 and March 3, urging the state to choose one of three reasonable options proposed by the petitioners: retain the flats by paying current market rent, purchase the flats outright or vacate the premises. With no meaningful response from the state, the court proceeded to pass final orders.

“In such circumstances, we need not hear the parties anymore on any other issues. We set aside the impugned judgment passed by the high court and allow the original writ petition preferred by the appellants before the high court. We grant four months’ time to the respondents [state government] from today to hand over vacant and peaceful possession of both the flats in question to the appellants along with the arrears of rent accrued till the date of handing over of the possession of the flats. We are informed that the department has not been paying rent since 2008. The rent shall be calculated accordingly and be paid to the appellants,” the apex court said in its order. The apex court also directed Deputy Commissioner of Police Nitin Pawar to file a sworn undertaking within a week to ensure compliance.

‘Happy we could do justice’

“We are happy that we have been able to do justice with the appellants who have been frantically trying to get back their property… It appears that the high court was hesitant to exercise its writ jurisdiction as it got confused on the aspect of the nature of possession. The high court found the possession to be permissive in nature. In such circumstances, the high court thought fit to relegate the appellants to avail alternative remedy of filing a suit,” reads the order of the Supreme Court.

The order further reads, “The high court should have kept the year [1940] in mind. The country was fighting hard to seek independence from the British. Bombay in the year 1940 was altogether different…” “To ask the appellants to file a suit and recover the possession would be like adding insult to the injury. At this point in time, if the appellants are asked to institute a suit, we wonder how many years it would take by the time the litigation would come to an end, if at all it reaches up to the highest court of the country,” the order reads.

Highlighting the broader constitutional implications, the judgment notes, “Injustice, whenever and wherever it takes place, should be struck down as anathema to the rule of law and the provisions of the Constitution.” “This is one of those cases wherein the high court should have readily exercised its writ jurisdiction. The constitutional powers vested in the high court or the Supreme Court cannot be fettered by any alternative remedy available to the party concerned,” the order states. The petitioners were represented by advocates Azmat Amanullah and Aishwarya Kantawala in the Supreme Court.

A watershed judgment

The verdict has been hailed as a landmark in the fight for private property rights and a strong assertion of constitutional safeguards against state overreach. Dr Kantawala, who led the legal battle in the Bombay High Court, described the historic verdict as “a triumph of perseverance and real and substantial justice which the common man expects from every court, in this case, by the highest court. This should have been the judgment delivered by our Bombay High Court. The tragedy is that not all have the capacity to approach the apex court” A senior officer of the Mumbai Police told mid-day, “We are taking a legal opinion and will file a review petition.”